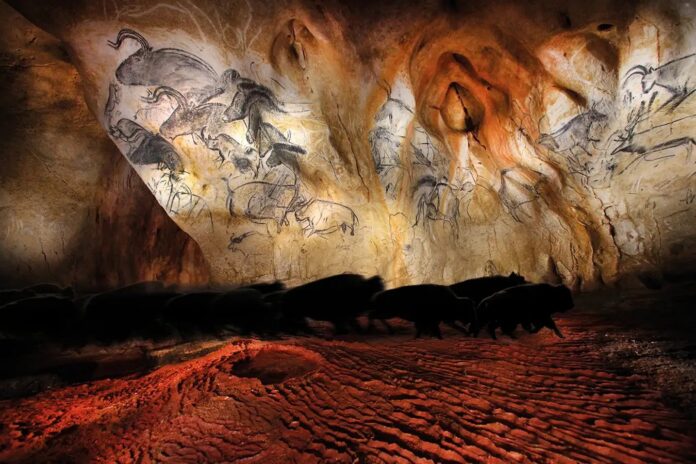

For millennia, the silent walls of prehistoric caves have held a secret: they weren’t just meant to be seen, but heard. Recent archaeological discoveries reveal that the placement of ancient rock art wasn’t arbitrary; it was deliberately chosen for its acoustic properties, transforming caves and rock shelters into immersive, multi-sensory spaces designed to amplify rituals, storytelling, and even altered states of consciousness.

The Echoes of Discovery

The idea that prehistoric art was intrinsically linked to sound began decades ago with French musicologist Iégor Reznikoff. His experiments, involving singing within Paleolithic caves, revealed a striking correlation between the placement of paintings and resonant acoustic phenomena. While initially dismissed as unrigorous, Reznikoff’s work laid the foundation for the emerging field of archaeoacoustics.

Later studies, including those by Steve Waller, documented echoes of up to 31 decibels at decorated spots in French caves, contrasting sharply with acoustically dead unpainted walls. Waller proposed that these echoing spaces may have been interpreted as the homes of thunder gods, embodied by the stampeding hoofed mammals frequently depicted in the art.

Systematic Investigation: Artsoundscapes and Beyond

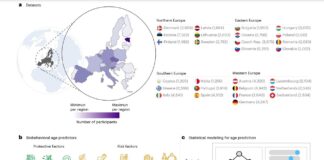

The Songs of the Caves project, led by Rupert Till, and the subsequent Artsoundscapes initiative, spearheaded by Margarita Díaz-Andreu, brought scientific rigor to the field. Using impulse response measurements and advanced modeling, researchers demonstrated a statistical link between rock art and “unusual” acoustic phenomena across continents.

The Artsoundscapes project revealed that prehistoric cultures around the world deliberately chose sites with specific acoustic properties. In Siberia’s Altai mountains, sites amplified sound clarity, suggesting they were used for ritual gatherings. In Mexico’s Santa Teresa canyon, paintings were found in locations ideal for ritual dances. Even in White River Narrows, Nevada, certain painted spaces were found to communicate acoustically with each other.

The Power of Resonance: Altered States and Ritual

The acoustic properties weren’t merely about amplification; they were about manipulating perception. Experiments at Finnish lake district rock faces showed that the disorienting sonic reflections created a sense of “presence,” even fear, as if someone else were nearby. Researchers at the University of Helsinki found that the auditory illusions activated the brain in ways that suggested a heightened emotional experience.

Neuroscientific studies further support this idea. EEG readings showed that frequencies near 110 hertz, common in low baritone chanting, deactivated language centers and boosted emotional processing in the brain. This suggests that rituals performed in these spaces may have intentionally altered consciousness.

Beyond Rock Art: Ancient Instruments and Sacred Spaces

The acoustic manipulation wasn’t limited to natural resonance. Archaeological finds, such as 35,000-year-old vulture bone flutes from Isturitz cave in France, suggest that ancient people actively created music designed to interact with these spaces. When played within the caves, the instruments produced soaring sounds that transformed the spaces into immersive, sonic environments.

Even structures like the 5000-year-old Neolithic tomb of Ħal Saflieni in Malta were engineered to be musical instruments themselves. The chamber’s resonant frequencies sustained drumbeats for up to 35 seconds, creating a powerful, immersive sonic experience.

The Ancient Symphony: A Multi-Sensory Experience

The evidence is clear: prehistoric art wasn’t just a visual medium; it was a key component of a carefully crafted, multi-sensory experience. By manipulating sound, ancient cultures amplified rituals, altered consciousness, and created spaces that were deeply connected to the natural world. The silent walls of the past are finally speaking, revealing a sophisticated understanding of acoustics that challenges our understanding of ancient societies.