Starfish, also known as sea stars, are surprisingly adept climbers. They effortlessly move across vertical, horizontal, and even inverted surfaces—rocky, slimy, sandy, or glassy—all without possessing a centralized nervous system or brain. New research sheds light on how these invertebrates achieve this remarkable feat: by adapting their movement based on immediate physical demands, rather than relying on central control.

Hydraulic Feet and Adhesive Slime

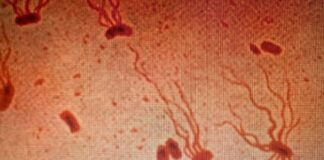

The underside of each starfish arm is covered in rows of hydraulic tube feet (podia). These flexible, muscular stems pump fluid through the starfish’s water vascular system to enable movement. At the tip of each stem is a flat, adhesive disk that secretes protein-rich slime for grip, and potentially another slime for detaching when necessary.

The common starfish (Asterias rubens ) uses hundreds of these tube feet to crawl, coordinating their timing without any central nervous system directing the process. The researchers found that larger starfish do not move slower, nor do more appendages slow them down: unlike most animals, size and limb count don’t dictate crawling speed.

How Researchers Studied Starfish Movement

To understand this decentralized locomotion, scientists used a unique method: illuminating highly refractive glass in a lab. When a starfish crawled across this glass, light refraction created bright “footprints” showing exactly which tube feet were engaged at any given moment.

The results revealed that starfish maintain a consistent crawling speed regardless of how many feet are in contact with the surface. However, increasing the contact time of each foot slows down movement. This suggests starfish regulate their gait by adjusting contact duration based on mechanical load, not through centralized neural commands.

Testing Mechanical Load with Backpacks

To confirm this theory, the team tested starfish with weighted backpacks, adding either 25% or 50% of their body weight. The extra load predictably increased the adhesion time for each tube foot, further supporting the idea that mechanical demand directly influences movement.

Experiments with inverted locomotion—starfish walking on “ceilings”—showed the same principle: tube feet adapt contact behavior based on gravity. This means starfish don’t need a brain to adjust to different terrains or orientations.

Decentralized Strategy for Complex Terrain

The research concludes that starfish navigate challenging surfaces through a robust, decentralized strategy. They modulate tube foot-substrate interactions in real-time, adapting to mechanical demands without relying on a central nervous system. This finding provides a fascinating glimpse into how complex movement can evolve even in the absence of traditional neural control.

The study highlights that starfish effectively “feel” their way through environments, adjusting their grip and timing based on immediate physical feedback. This decentralized approach is a testament to the power of simple biological mechanisms in solving complex locomotion challenges.