For centuries, scientists have known that gravity affects all objects equally, regardless of their mass or composition. This principle, known as the weak equivalence principle, is a cornerstone of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. Now, a landmark experiment confirms that even antimatter – one of the most exotic substances in the universe – behaves according to this rule, falling downward just like ordinary matter.

The Historical Context: From Galileo to Einstein

The concept of universal gravitational acceleration dates back to Galileo’s experiments, where he demonstrated that objects of different weights fall at the same rate in a vacuum. Einstein didn’t attempt to explain why gravity affects everything equally; he simply assumed it as a fundamental law when formulating his theory of general relativity. This assumption has held for all observed matter until recently.

The Antimatter Puzzle

Antimatter, predicted by physicist Paul Dirac in the 1920s as a consequence of reconciling quantum mechanics with special relativity, presents a unique challenge to this understanding. Dirac’s equations suggested that for every particle, there exists a counterpart with opposite charge but identical mass. When matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate each other, releasing energy. This makes studying antimatter’s gravitational behavior incredibly difficult.

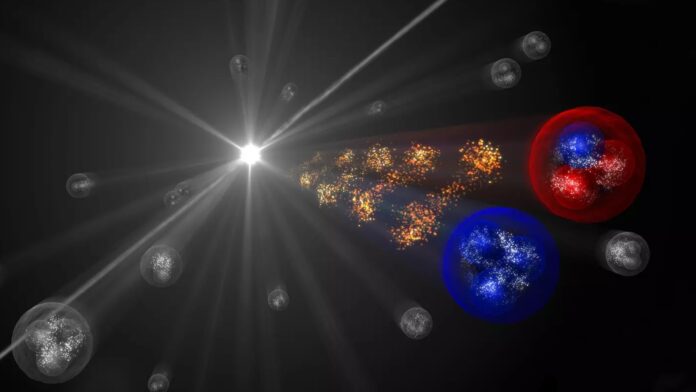

The ALPHA-g Experiment at CERN

Scientists at CERN’s ALPHA-g experiment overcame these hurdles by creating neutral antihydrogen atoms – pairing antiprotons with positrons (anti-electrons). These neutral atoms, unlike charged antimatter, aren’t affected by electromagnetic forces. To isolate antimatter, researchers used a “Penning trap” – a magnetic bottle to hold them in place – and cooled the antiatoms to near absolute zero to minimize movement.

The Results: Antimatter Falls Downward

By gradually weakening the magnetic field, the team observed the behavior of the trapped antihydrogen atoms. If antimatter defied the weak equivalence principle, it might have drifted upward due to some unknown repulsion. Instead, approximately 80% of the antiatoms fell through the bottom of the trap, annihilating upon contact with the container walls. This confirms that antimatter is pulled downward by gravity, just like ordinary matter.

What This Means for Physics

The experiment doesn’t prove that gravity and quantum mechanics agree —they still speak different languages. But it does reinforce Einstein’s theory of general relativity by showing it holds even for antimatter. However, the case isn’t entirely closed. Researchers haven’t yet determined whether antimatter falls at the exact same acceleration as matter. A slight difference, even 1%, would require a fundamental rethinking of gravity.

For now, the universe remains consistent: hammers, feathers, and antihydrogen all fall at the same speed. This is not a revolution in physics, but a reassuring confirmation that the universe behaves as we expect.