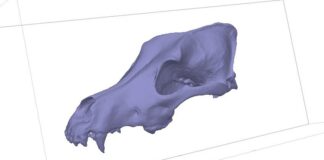

Bonobos, one of our closest primate relatives, exhibit the ability to engage in imaginative play, a cognitive skill previously thought to be exclusively human. A new study provides the first rigorous experimental evidence that these apes can understand and track pretend objects in controlled scenarios. This suggests that the capacity for imaginative thinking may have evolved much earlier in our shared evolutionary history than previously assumed.

The Experiment: How Bonobos “Pretend”

Researchers tested Kanzi, a deceased bonobo renowned for his advanced cognitive abilities, using a series of carefully designed experiments. First, Kanzi was trained to point to cups containing juice as a reward. Then, scientists pretended to pour juice into empty cups, manipulating the scenario to trick Kanzi into identifying which cup held the imaginary liquid.

Remarkably, Kanzi correctly selected the “full” cup in 34 out of 50 trials. This wasn’t about learned behavior – Kanzi received no reward for correct answers, eliminating the possibility of simply mimicking human cues.

To ensure Kanzi wasn’t confused by real juice, the experiment was repeated with one cup actually containing liquid. In 14 out of 18 trials, Kanzi chose the cup with real juice, proving he could distinguish between tangible and imaginary contents. A third test confirmed Kanzi could identify the location of a nonexistent grape in a transparent container.

Why This Matters: The Roots of Imagination

The study’s findings matter because they force us to rethink where imagination comes from. For decades, scientists assumed imaginative play was a uniquely human trait. Now, we see that bonobos, who share roughly 98% of our DNA, can also follow imaginary scenarios.

Dr. Amalia Bastos, the lead researcher, suggests this ability likely dates back to our last common ancestor with bonobos, between 6 and 9 million years ago. This means the foundations of imaginative thought aren’t a recent development; they’re deeply rooted in primate evolution.

Beyond Kanzi: What This Means for Ape Cognition

While Kanzi was exceptionally well-trained to interact with humans, the results still offer a groundbreaking insight.

Prof. Zanna Clay of Durham University notes that while more research is needed on wild or less-trained apes, the study challenges the notion that imagination is something exclusive to humans. Given the complex social and ecological pressures apes face, it would be more surprising if they lacked this cognitive flexibility.

As Bastos and Krupenye conclude, the capacity for representing pretend objects is not uniquely human, suggesting a broader evolutionary link between imagination and primate intelligence.

This discovery isn’t just about bonobos; it’s about understanding how the human mind evolved. If our closest relatives can engage in imaginative play, it suggests that this ability wasn’t a sudden leap forward but a gradual development shaped by millions of years of primate evolution.