Early dogs, even those living over 10,000 years ago, exhibited a remarkable range of physical forms, challenging the long-held belief that modern dog breed diversity is a relatively recent phenomenon originating in the Victorian era. A new analysis of canine skulls spanning 50,000 years reveals that significant variation in dog morphology existed long before standardized breeding practices took hold.

Early Variation Was Already Present

Researchers found that by 10,000 years ago, roughly half of the physical diversity seen in dogs today was already established. This discovery fundamentally alters the understanding of how dog breeds evolved, suggesting that natural selection and early human-animal interactions played a more substantial role than previously thought. The study, published in Science, divided specimens into those from the Late Pleistocene (over 12,700 years ago) and the Holocene epoch (less than 11,700 years ago) to track changes over time.

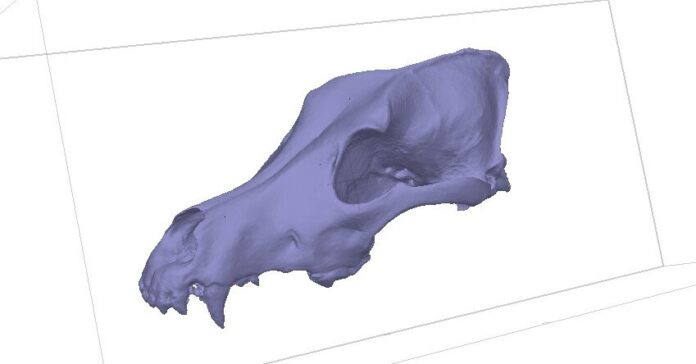

Skull Shapes Differed Significantly

Older canid skulls tended to be streamlined and slightly larger, while more recent specimens displayed greater variation in both size and shape. Some younger skulls were noticeably shorter and wider, indicating a broader range of physical traits even in ancient populations. While extreme features like the flat faces of modern breeds (e.g., Pugs) were absent in archaeological specimens, some skull shapes found in older dogs have disappeared from modern breeds entirely.

What Drove This Diversity?

The reasons behind this early variation remain unclear, but a combination of factors likely contributed. Ancient wolves themselves were already diverse, and living alongside humans may have allowed less-competitive canines (like those that would struggle in the wild) to survive. Domestication, in essence, created a niche where a wider range of physical forms could persist.

Human Migration and Trade Played a Role

The increase in dog diversity coincided with significant human migration patterns across Eurasia. Humans likely brought dogs with them, and some societies may have even traded them, leading to further genetic mixing and physical variation. Different human groups bred dogs for different purposes, adapting them to their specific survival needs and production activities.

Early Dogs vs. Wolves

The study also clarifies the distinction between early dogs and wolves. Older canid skulls (over 15,000 years old) closely resemble those of wolves, suggesting that the transition to domestic dogs was gradual and that some previously debated specimens may not have been fully domesticated. The earliest distinctly doglike skull identified in the study dates back roughly 11,000 years.

This research demonstrates that dog diversity is not merely a product of Victorian-era breeding but a long-evolving trait shaped by natural selection, human interaction, and migration. The findings challenge the assumption that modern breeds represent the pinnacle of canine evolution and highlight the complex history of the human-animal bond