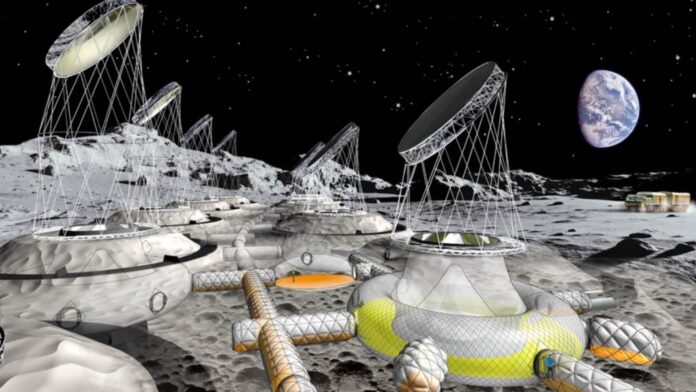

The 21st century marks a turning point in lunar exploration. Unlike the Cold War-era race to the Moon, today’s ambitions extend beyond symbolic victories – multiple nations now aim to establish permanent bases on Earth’s natural satellite. This shift introduces a critical question: how can spacefaring nations avoid conflict over limited lunar resources and strategically valuable landing sites?

The Emerging Lunar Landscape

The South Pole of the Moon holds the key to sustainable lunar operations. Abundant water ice, locked in permanently shadowed craters, can be converted into water for human consumption and rocket propellant, fueling ongoing exploration and long-term habitation. Beyond water, valuable minerals like rare earth metals further incentivize lunar resource extraction. However, these resources are finite, and suitable landing/base locations are limited, creating a potential flashpoint for international competition.

The Legal Framework: A Patchwork of Treaties

The foundation for governing space activities lies in the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which prohibits national appropriation of space through claim of sovereignty or occupation. This treaty establishes space as a global common, intended for peaceful exploration and benefit for all nations. However, the application of this principle to lunar resource extraction remains ambiguous.

The 1979 Moon Agreement reinforces the non-appropriation principle but lacks broad support, with major spacefaring nations like the US, China, and Russia notably absent from its signatories. The US-led Artemis Accords, a more recent framework, attempt to establish practical guidelines for responsible lunar behavior. Section 10 of the Accords asserts that resource extraction does not constitute national appropriation under the Outer Space Treaty.

The Accords propose temporary “safety zones” around resource extraction operations to avoid interference, but these zones are controversial, potentially blurring the line between responsible utilization and de facto ownership claims. As of late 2023, 38 nations have signed the Artemis Accords, including Thailand and Senegal, which participate in both the US-led program and China’s International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) project, signaling a willingness to bridge the two competing initiatives.

The Race to Establish a Lunar Presence

China, along with a consortium of ten nations, is developing the ILRS, while NASA is pushing forward with the Artemis Base Camp. NASA’s Artemis II mission, scheduled for February 2026, will carry four astronauts on a lunar flyby, and a new class of astronauts was announced in September 2023, likely to participate in future surface missions. China recently completed a test of its crewed lunar lander, Lanyue, and the ILRS project actively recruits nations with less extensive space exploration experience.

Avoiding a Lunar “Wild West”

The key to preventing conflict lies in moving beyond zero-sum competition. Replicating the historical “land grab” mentality of Earth-based exploration is unsustainable in the 21st century. All humans on the Moon will be “terrestrials,” regardless of national flags. Space can serve as a platform for diplomacy, socio-economic development, and collaborative scientific advancement.

A Path Forward: Transparency, Cooperation, and Adaptive Governance

Expanding humanity’s footprint beyond Earth is the defining challenge of this century. A global effort to explore outer space collaboratively and peacefully is not just possible; it is mandatory. Nations should prioritize transparency, adherence to existing treaties, and a willingness to adapt governance structures as lunar operations evolve.

The Moon Agreement, despite its limitations, offers the best existing framework for responsible lunar governance. Rather than pursuing new treaties, nations should focus on utilizing and refining existing agreements. The future of lunar exploration hinges on embracing cooperation, not competition, ensuring that the final frontier remains a realm of shared human progress