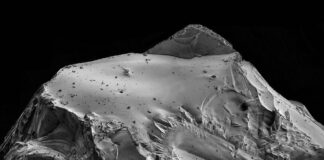

A massive hillside in Peru, covered by over 5,000 aligned holes arranged in a snake-like pattern across its slopes, may have been an unprecedented accounting system used by the Inca Empire. Known as the “Band of Holes” on Monte Sierpe (Serpent Mountain), this enigmatic feature has baffled archaeologists since its aerial discovery in 1933.

Initially, theories about the holes’ purpose ranged from burial sites or defensive structures to water storage or agricultural use during the flourishing Inca era (1438-1533). But new research using drone imaging and sediment analysis suggests a far more complex explanation: this massive arrangement of depressions, each roughly 1 to 2 meters across and between 50 centimeters and 1 meter deep, might have served as a monumental spreadsheet.

Jacob Bongers, an archaeologist at the University of Sydney and lead author of the study, explains, “This 1.5-kilometer-long band of holes has baffled people for decades.” The recent analysis focused on samples from within 19 holes and provided a clearer picture of their layout using high-resolution drone imagery. The results revealed pollen grains of both cultivated crops – maize, amaranth, chili peppers, and sweet potatoes – and wild plants like bulrush, traditionally used in basket weaving and raft construction.

Crucially, the pollen distribution rules out wind dispersal as a factor. Bongers postulates that local Chincha groups – who inhabited the region from around AD 900 to 1450 – lined the holes with plant materials and deposited goods brought from surrounding agricultural areas. These offerings likely arrived in woven baskets transported by llamas, explaining the relative scarcity of pottery at the site. “The data support the idea that people brought goods to the site and deposited them in the holes,” Bongers states.

“We think it was initially a barter marketplace. That was then turned into a sort of large-scale accounting device under the Inca.” – Jacob Bongers, University of Sydney

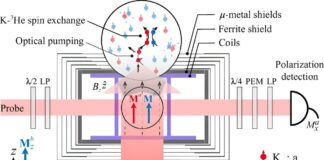

Around 1480, the Chincha came under Inca dominion, retaining their autonomy while also contributing levies as required by the burgeoning empire. The “spreadsheet” hypothesis arises from the precise counting of holes enabled by aerial imagery (approximately 5,200) and variations in their organization. These sections, at least 60 in number, mirror the structure of knotted string devices known as khipus, which the Inca used for calculation and record-keeping. While khipus have been likened to calculators or abacuses, Bongers proposes that the hole layout better resembles a spreadsheet meticulously recording tribute collections from diverse local communities.

The distinct sections likely corresponded to specific groups inhabiting the fertile Pisco and Chincha valleys, where an estimated 100,000 people resided near Monte Sierpe at the time. One khipu displaying similar structural divisions was discovered in the Pisco valley, divided into approximately 80 sections compared to the site’s 60-odd blocks.

While intriguing, this comparison isn’t straightforward. Karenleigh Overmann, an archaeologist at the University of Colorado, notes: “The holes are organized into 60-some sections and the khipu is organized into 80, and that’s a pretty big difference in numbers.” She also raises questions about the decimal organization expected within Inca systems, given that the hole layout doesn’t strictly adhere to groupings of ten.

Bongers acknowledges these points, suggesting that the site may have evolved over time alongside changes in its usage or potentially matching khipus. “We’re seeing the final form, but it could have started out as just a couple of sections and changed over time with the population,” he proposes.

The strategic location near intersections of pre-Hispanic roads and between significant Inca administrative centers – Tambo Colorado and Lima La Vieja – further strengthens the argument for centralized tribute collection.

While Overmann commends the study’s meticulous elimination of alternative theories, she suggests a simpler explanation: “There is a lot of tradition in Peru of making giant petroglyphs that can be seen from a distance,” she points out. “Maybe they were just doing that.” Bongers readily concedes this possibility but emphasizes that both explanations could hold true.

“Two things can be true at the same time. It’s a big, giant snake, but it served a functional purpose, so I see this site as a sort of social technology.” – Jacob Bongers

In essence, for societies lacking modern communication tools like the internet or cell phones, a colossal landmark visible from miles around could serve a dual purpose: both symbolic and practical. It would function as a meeting point and focal point for complex societal transactions like tribute collection and record-keeping.

This extraordinary hillside installation on Monte Sierpe pushes the boundaries of our understanding of Inca social organization and administrative ingenuity, demonstrating how they harnessed monumental architecture to manage vast territories and diverse populations. Further research will undoubtedly shed more light on this remarkable testament to Inca civilization’s technological sophistication.